» #96 is available now!

Issue #96 features fiction by Jennifer Worrell, Ian Cockfield, Nickel Rockel, and Charles Tidler; commentary by Peter Babiak; creative non-fiction from Geoff Inverarity and Jane Silcott; poetry by Henry Doyle, Eve Joseph, and John Pass; and the Winners and Runners-up of the 2023 Lush Triumphant Literary Awards: Rishi Midha, Erin McNair, Adrienne Gruber, Lisa Sisler, Kate Rogers, and Laura Fukumoto. Reviews of new books by: Lyndsie Bourgon, Ewan Clark, Peter Counter, Tim Blackett, Emily Riddle, Martin West, Barbara Pelman and edited by Michel Jean (translated by Kathryn Gabinet-Kroo), and our regular columns, Chuffed About Chapbooks by Kevin Spenst and The Crank & File from Matthew Firth.

Pick up a copy wherever good lit-mags are sold. Or order a sample copy from our website!

The Editors

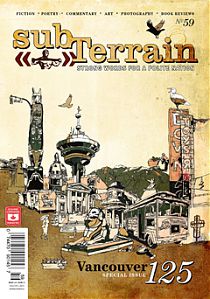

Cover and interior illustrations by Robert John Paterson.

Give a subscription of subTerrain as a gift to someone you love—even yourself. Extended until January 16, only $20 for two years.

Darryl Gillingham illustration

» Fiction

One on One

The last time I saw Trisha we were supposed to get together for some noose-play. The format was usually the same. I’d go over to her place. She’d drag out her slutty leather dress, black stilettos and rubber top. We’d smoke a joint then have a glass of wine and pretty soon the porn would roll out: Gallows Girls, Date with the Hangman or else some strangulation clips she’d pieced together from various horror movies and put onto a CD.

Once she got high she’d moan and that was my cue. I’d strip down naked and get on my knees. Trish would tie me up and walk around the room with her heels clicking on the hardwood floor. Then she’d examine my physique like it was a laboratory specimen, pull out the rope from her cedar chest and prepare the noose with painful precision. She was into detail. Either I’d end up by choking out right away or else she’d toss the other end of the rope over a ceiling beam. Either-or, it was lights and sirens all the way.

I’d been into asphyxia as long as I can remember, probably way back into childhood. My first memory of sexual excitement was watching the hanging scene in Cat Ballou when Jane Fonda gets noosed and then rubbing my crotch on the shag carpet of our living room floor.

Transsexuals were something I was never really into. Not that I knew of, anyway. Sure, I’d seen them in porn magazines but in small town Alberta we didn’t have many working in grocery stores. Finding women who were into kinky stuff was a pretty tall order and I was tired of dating columns, web sites and tennis games that ended in agricultural discussions. Beggars couldn’t be choosers. Pro dommes were okay, but you had to drive all the way into Calgary for that. They charged a lot of money and came with their own set of troubles.

On the last Sunday of every month the Black Rhino Pub and Western Grill had a costume night and most of the kinky folk in the Red Deer valley went there under the guise of “dressing up.” No one else drank on a Sunday night in our town so management posted a cover charge and let us do what we wanted. The owners begrudgingly enforced a dress code that kept the soldiers from Suffield at bay.

The first time I saw Trish I thought she was a girl. She leaned over the bar with a champagne cocktail and had on a black mini skirt, white blouse and blue wig. She was beautiful really, too much makeup, but stunning. Lithe, thick-lipped, something you’d expect to see on that old British television series UFO where all the spacewomen had big boobs, blue hair and Lycra spacesuits.

“That’s nice hair,” I said.

“Thank you,” she said back.

Up close you could tell: Adam’s apple, strong hands and a voice pitched halfway in the wrong direction, but by then I was already in far too deep to back out.

Talking kink to strangers was fair game at the Rhino. Essentially that’s why people went even though most of them were wannabes. Small talk was just a waste of time.

“What are you into?” I asked her.

“Role play,” she said. “Breath control, asphyxia. I like scenes with a beginning, middle and end. You know, narrative.”

Then she giggled and bit on her string of white pearls. If there had been a lightning rod outside, I would have been fried. This was the grand prize, the Lotto Max. Well, maybe the Lotto Mini Max because the pure gold would have been a woman, but what the hell this was good. What she had between her legs simply didn’t matter.

“Fabulous,” I said. “Do you like noose-play?”

“Oh yes. I used to watch westerns when I was a teenager. My mother thought I was into horses.”

“I think we’ll get on.”

Trish sized me up, considered her options then glanced around at the competition. The bar was filled with a number of overweight oil riggers, some obviously disturbed kinksters with prosthetic limbs and a few newbies who looked very nervous. The men outnumbered the women, the women called the shots and most people’s idea of kink in the Red Deer valley was doing missionary in the barn.

“You don’t mind?” she said. She held up her cocktail and stared at the olive so the sentence didn’t need to be finished.

“You’re gorgeous.”

Her eyelashes fluttered. Her gold fingernail circled the rim of her glass.

“You’ve done a T-Girl before?”

“Sure,” I lied. “Had playmates in Calgary. Pretty low-key there. You don’t see many cross-dressers at the stampede.”

She laughed. I got a drink. The bartender stood on the other side of his fence expressionless. He had been given strict instructions by the management to stay non-judgmental, shut up and collect the tabs.

“Have you played with anyone here?” she said.

Okay, I’d gotten to know a few friends here. Sal, the blonde who was drinking scotch at the One Armed Bandit, I dated but that didn’t work out. Sal liked ponies way too much. Jen, a tall brunette in her fifties, stood by the jukebox in her rubber suit. Architect by trade, she was into flogging, which I liked, but she was looking for a husband and I wasn’t. Tom and Terry were gay. Not that that bothered me. They liked to talk about rodeos and came to the club together because this was the only place in town they could act natural. Pam, a woman my age with red hair, walked past us and lifted her glass. She was athletic, into just about anything, but she was also the most sought after commodity in the circuit, knew it, and so I didn’t bother. I’d been down that road before.

“Nothing serious,” I said. “Pam’s okay to look at but that’s it.”

“Trouble.”

“Really?”

“I mean I’ve got nothing against her personally, but there’s a lot of estrogen flying around in that chassis.”

“Bi?”

“Mmm,” Trish said. “Drama queen. The lengths she’ll go to are unbelievable.”

“Whatever.”

The evening wore on and somewhere around Tom Collins number four it dawned on me that Trisha’s real name was Tad and he worked in the Chamber of Commerce. Great looking guy but I’d only ever seen him from a distance and, besides, at the club you didn’t talk about what went on in vanilla life. Rule 1(a): No blabbing. I checked my watch.

“What do you think?” I said.

She bit her pearls again and stared at the ceiling.

“Do you want to go to my place?”

I waited the compulsory one-point-five seconds.

“All right,” I said.

“Me topping you. Me on top all the way since it’s our first time.”

“Sure.”

This was an absolutely ludicrous thing to consent to. Going to a complete stranger’s house by yourself and being on the receiving end of some very dangerous technical work was not a street-smart decision. There are probably stats on how many people die each year with ropes around their necks, but I didn’t care. I convinced myself that her deference rendered her harmless. Saying I was so big and strong that I had to be on the bottom. And then it just didn’t matter. I took her hand and we walked to the front door. Her shoulder smelled of lime. All the would-be perverts in the bar eyed us with needy condescension and Trish gave someone in the corner a screw-you wave.

Trish’s house was a wartime bungalow on the industrial side of the tracks. Lots of creosote, railway ties and abandoned grain silos. The stucco was grey and the sidewalk patiently cracked. Out front there was a bed of weeds and a lonely thistle garden. She drove her truck around back and parked down the alley that was encased in caragana.

“Neighbours,” she said. “There’s just no point in parking out front.”

The inside of the house was sparse and lonely. A couch, a cold hardwood floor and a couple of black books on the shelf detailing public planning policy. We went straight downstairs. Downstairs was where the action happened. Downstairs was it. Teak floor, big screen TV, air ionizer, full spectrum lighting and a couple of telltale hooks hanging from the beams that couldn’t be used for potted plants. The door to the playroom had a window in it and also a lock.

“I cook upstairs,” she said. “This is where I live.”

She turned on the lights, closed the curtain and leaned back on her IKEA sofa.

“Joint?” she said.

“Why not?”

Trish lit up. Hard to tell if her tits were implants or falsies. Didn’t matter. The cold hardness of desire swept over her face and she stretched her long legs on a pillow. Her makeup made her look Oriental.

“Strip for me,” she said.

Part of the kinkster game is you can do all kinds of over-the-top stuff and get away with it. Stuff that would get you thrown out of a grade eight drama class is prime time here. I stripped down and stood straight out, pounding, aching, stretching and making all the air in the basement reek of testosterone. Then I got down on my knees and kissed her shoes. The skin on her calf was tanned and amazingly smooth. Somewhere in the last thirty seconds she had lost her nylons. She got up, walked around behind me and tied my hands behind my back with a hair dryer cord. Then she pulled a thick cotton rope out from a cedar chest and bit on the end. I got all the technical details of the rope’s weight, diameter, hemp content and load limit. I’ll never forget her made up face absolutely perfect in want, the black pupils searching deep and insect-like into a need of mine no one else had ever seen. She fastened one end of the rope around the beam in a half hitch and the other around my neck. Then she pulled up her dress. Champagne bubbles burst in my head, my throat filled with salt and an alarm clock went off as my skull hit the floor.

“How was that?” she said after. She lounged on the sofa with another cocktail and her toenails had pink lilies painted on them.

“Fabulous.”

“I think I’ll keep you.”

The next day, I saw Pam in the bank. I knew she was going to break a cardinal rule of the club but she strolled up to the cheque-writing counter and stood way too close to be anything but sexual.

“How did it go last night?” she said.

I gave her a blank stare. She had a yellow rodeo scarf wrapped around her neck like a lot of tourists did in the middle of the summer and cowboy boots that probably hadn’t been out of their box in years.

“Fine.”

“I’m sorry I didn’t get a chance to talk to you last night,” she said. “Didn’t want to interrupt. Got time for lunch?”

“I guess.”

“Why have you been ignoring me?”

This seemed to be pretty much a law of the kink universe. You’d spend years looking for people in solitude, going to stupid socials, attending workshops, answering ads, and nothing, nada, nyet, then all of a sudden you got lucky and everybody wanted a chip of the action. We went over to the Big Horn for a Bronto Burger and got a booth. Pam smelled of lilac perfume, something French anyway. She had delicate features, a small nose, and in the daylight her hair was the same colour as a barn on fire. She held her fingers up in an okay sign as she ate so she wouldn’t get mayo on the table and quizzed me about my nocturnal encounter.

“I didn’t take you for the bi type,” she said.

“I’m not.”

She gave me a queer look and asked for another Pepsi.

“Please,” she said.

“Trish and I just had a lot in common.”

“Uh-huh.”

“She’s a nice lady.”

Pam raised an eyebrow and agreed on the pronoun according to protocol.

“I guess I just know the other side of her,” she said.

“Which side?”

“The Tad side.”

I shrugged. Like I fucking cared.

“You’ve done the plastic bag routine with her?” she asked.

I dished out the “gentlemen don’t tell” smile.

Pam wasn’t giving up. She wanted content. Some of the mayo stuck to her chin and she made a point of shoving her index finger down her throat to clean it up.

“She likes the One Hour Martinizing bags because they cling,” she said.

“Really.”

“But she plays rough. Don’t get me wrong. I like rough.”

The words lingered for a dramatically long time. “In fact, I like almost everything. Watching, too. But look after yourself. Have a good fail-safe system in place is all I can say.”

She took a menthol cigarette out of her purse, tapped the end of the tabletop, but didn’t light up. A sign above the door said No Smoking. $200.00 fine.

“Are you a pro?” I said.

“A what?”

“A Pro domme.” Calling someone a whore was rude but a Pro domme had a ring of aristocracy. “I mean not at this minute, but at some time in the past? You just have that air about you.”

What I was actually saying in code was you are being a bitch, but Pam didn’t take the bait.

“Can you play tennis?” she said.

“Yes. Of course I can play tennis.”

“No, I mean can you really play? Are you any good? Not can you put on a pair of white shorts and look smart. It’s tough finding good players around here. All the guys want to do is cattle rope and they get their dicks stuck in the net.”

“I’m good,” I said.

“Up for a game some time?” She studied her unlit cigarette. Her red nails were perfectly manicured. “Just tennis. That’s all I’m looking for. I know you’re taken.”

“Sure,” I said.

“You don’t mean that.”

“I do.”

“Ten bucks a game?”

I went home and practiced against the wall. About three, the kink creep started inside me and all I could think about was Trish’s tanned legs and fake Georgian accent. She worked at the bank until four, but I knew I couldn’t go there. Didn’t want to show up at her place unannounced and most certainly didn’t want to wait until the end of next month to get done again. I wrote my name and number on a piece of paper and wedged it into her back door. Some hornets had made a nest beneath the soffit. By six the phone rang.

“Hey baby,” she said.

“Hey,” I said.

There’s a point in any conversation when it becomes all about sex and we had already reached that point.

“What are you up to?” I said.

“Waiting for you.”

“When?”

“Give me half an hour. I have to get made up.” Then she paused. “Do you have a car?”

“Sure,” I said.

“Can you pick up a prescription for me at the drugstore?”

“Of course.”

“Then park out back, okay?”

When I went downstairs the air already reeked of hemp. Fleetwood Mac was on the stereo and some very nasty porn was on the huge television. A nude man slicked down with oil was being garroted by a woman in a witch costume.

“Hey hon,” the voice said from the off-suite.

“Hey,” I said.

“What to wear to a hanging,” Trish said and came out of the room in five-inch heels and a fishnet body suit. She wrapped her fingers over the doorframe and I knew I wasn’t going to have much say in what happened next.

A lot of the times I’d wake up the next day with a searing headache. My right eye would go out of focus. Rope burns too. I took to wearing high collar shirts to work which was stupid in the middle of July and everyone just assumed it was a hickey. One of the girls in the office kept giving me knowing grins. My short-term memory faltered, I’d been choked out four times in the past two weeks and I got pretty sure that Trish was probably hot waxing me while I was under. I got used to the after effects, but from time to time things got scary. Loud bells would go off in my head during hangings, shapes would flit by in the room so fast I couldn’t make out what they were, and often I heard people laughing above me when I was collapsed on the floor.

“Was there someone else in the room last night?” I asked Trish.

“Who?”

“I have no idea, who?”

She shook her head. “I don’t do that.”

“I thought I could hear voices. Up above.”

“That’s pretty common,” she said. We were watching a video from The House of Gaspers where a pretty blonde from Toronto pushes a man off a stack of telephone books and strings him up while wearing lace gloves. “Do you want to stay the night?”

That came down like a thistle in a corn dog.

“Uh, no,” I said. “Thanks, but I don’t think so.”

Trish put her hand on my knee.

“Okay,” she shrugged.

Pam had beat me three sets in a row and it was thirty degrees in the shade, which there was none of. She had on a white tennis top, white dress and one of those sweatbands around her head that people wear on Viagra commercials. Basically she was a poster girl for any Ivy League college in the country and I owed her thirty bucks.

“Give up?” she said.

“No, but I have to go.”

“Where?”

“Got a date.”

I bent over to pick up a stray ball and she struck me on the ass with the racket.

“You two spend a lot of time together,” she said.

“Do we?”

“You spend the night, don’t you?”

It wasn’t a question.

“Not often,” I said.

“Really?”

“That kind of stuff isn’t for me.”

“Don’t tell me,” she said. “You’re just in it for the sex.”

“Aren’t you?”

Pam went over and leaned against her red Volvo. Her skin was dark and covered in sweat.

“Yes,” she said. She opened the trunk and pulled out an ice sack. Inside there were two orange popsicles and she handed me one. “What’s on the agenda for today? If you can be so blunt.”

“Not sure,” I said. “Too rough for you, anyway.”

“Doubt that.”

“Mm.”

“No,” she said. “Call him.”

“She’ll say no.”

“He’ll say yes. He always does.”

“Not today.”

She opened the car door, took out her cell phone and tossed it to me.

“I know what you do and I know Tad. Call him.”

I dialed the number and waited.

“Hey hon,” she said.

“Hey, listen. I’m running a bit behind. Got to have a shower.”

“Come over sweaty. I like sweaty hunks. We can do a medieval scene.”

“Not this sweaty. Give me half an hour.”

“I’ll be ready when you get here,” she said.

Pam examined the threads on her racket then looked up.

“Hey, listen,” I said. “Is it all right if Pam comes over?”

“Pam?”

“She said she wanted to watch and that she knows what we do. I don’t know if you’d be into that or not.”

Trish thought for a long time.

“Whatever,” she said.

We had a shower at my place and Pam made a point of leaving the door open when she got wet. Everything that wasn’t freckles on that girl was red; lips, nipples, hair, even eyes when the bathroom light hit them the right way. Then she talked me into a scotch and soda and after we stuffed our tennis clothes into the trunk because she said she’d dry clean them for me. On the way over she gave me a litany of her asphyx experiences, which sounded canned, but the oil she’d smeared on her legs sparkled diamonds in the sun and I made a wrong turn at Trisha’s street.

“Better park around back,” she said.

“You know the routine, do you?”

“I know.”

I had this scene replaying in my head of Pam screwing me while I was choked out and knocked over a garbage can. The cottonwoods were drooping and covered in dust. The back alley hadn’t seen another car in days. We walked across the unkempt yard. The grass was long and yellow. A birdhouse once painted red was sun-worn to off-pink.

“She needs to do some yardwork,” I said.

“Too many hormones,” Pam said.

“Hormones?”

“They cut down on your desire to complete tasks.”

“Never had that problem with me.”

“Don’t shoot your load too fast, okay? I want to have some fun.”

We got up to the door and I had this bad feeling she might just mean screwing vanilla-style so I said, “Are you sure you’re into this?”

“Relax,” she said. “You have no idea. Don’t sweat it. It’ll all be good.”

But as soon as we got inside we both knew it wasn’t all good. A fan circling above the lonely dining room table made no noise. The air was stagnant. There was one plate, one teacup and one napkin. No stereo, no porn playing, no sounds of Trish clicking her shoes or buckling up the chrome latches on her leather corset.

“Trish?” I called out, no answer. “Hey hon, you ready yet?”

I realized I’d called her hon. Pam shuffled her purse between her palms checked the fridge and we went down the stairs. A newspaper from August, 1945 had been stuffed in the wall for insulation. At the playroom, the door was locked. Pam shot me a quick glance; I’d seen that glance on wheat buyers faces right before they knew the market was going to crash and I gazed through the window.

Trish was buckled down on her knees with the rope cinched around her neck. Her face was white as a mannequin and her dress was pulled down to her thighs. Something shriveled and pink had caught in the zipper.

Pam looked away for half a second and I panicked for a knife or anything to cut Trish down with. I was just about to pick up a screwdriver from the end table when Pam grabbed my arm.

“What are you doing?” she said.

“Cutting her down.”

“Don’t go in there,” Pam said. “Jesus, she’s been dead for an hour.”

Not much doubt about that. The face utterly plastic, bloodless and strangely masculine stretched beneath the blue wig.

“We’ve got to do something,” I said.

“Like what?”

“Call someone.”

“Not here,” she said. She put a finger to her lip. “We’ll go down to the pay phone and call.”

“Are you out of your mind?”

Pam was whispering in a loud hoarse voice which was louder than if she’d been just talking.

“No, I’m very much in my mind. Not all my blood is in my dick. Listen to me and listen good. There’s no need for us to get tangled up here. She’s dead. I’m sorry for it but don’t want to spend the next five days answering a bunch of questions from the medical examiner and half-a-hundred cops.”

“We can’t just leave.”

“I am. You are too. Don’t touch anything. We’ll walk out the back door back to my car and leave. Nobody will even know we were here. Don’t be stupid.”

We walked out of the room, shut the door and walked through the caragana bushes. My mouth tasted of ash. In the small town dust bowl that was Trish’s neighbourhood only a magpie saw us ditch the screwdriver in a grain silo that had been deserted since 1953.

Pam stopped the car at the 7-Eleven because I was too shaky to drive. When there was no one around, she went to the phone booth and dialed the police non-emergency line. She took a piece of tinfoil from her purse and put it over the receiver.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m calling from out of town. I’m just in visiting. I got a phone call from a relative who’s got a lot of psychological problems. He didn’t sound right. Can you go and check on him? Nothing serious probably, but he has a history.”

She gave the address and then hung up. We drove to the tennis court and put on our sweaty, stinking whites and played tennis for the rest of the afternoon, and more than a few people saw us there batting the ball around and laughing and commented on what a handsome couple we were. »

Small, Malicious Planet

What were the odds? Her? Here?

Wexler has long forgotten her real name. When he dreams her, she’s either Catherine T., or the-most-beautiful-girl-in-the-world-you-just-want-to-take-home-and-scrub-clean. Because the last time Wexler saw her, almost twenty years ago now, there had been something distinctly cruddy about her despite that face, stunning with its origami angles and inset with otherworldly eyes that gave her the look of a startled Japanese anime character — Sailor Moon as squeegee kid.

The long, ash-blonde dreadlocks are gone, replaced by a brown bob. A mom hairdo. Or MAWM! as the Brady kids used to say. He sees no signs of the aggressive hardware that had jutted from her eyebrows, nose, and lower lip, or the tattoos that swarmed her exposed flesh. She’s not in the resort’s requisite sarong and bikini top but wears a pale-blue ladies golf shirt and a pair of well-ironed khaki shorts that look alarmingly like Tilleys. In fact, the woman standing beside Wexler’s beverage shack on this Southeast Asian beach is so straight-looking she could have stepped out of a CIBC pamphlet pushing flexible G.I.C.s. But he can tell from those eyes and those facial bones that it has to be her. Catherine T. An exfoliated, repurposed Catherine T.

Wex fusses with a plastic-pineapple-tipped toothpick, stabbing at some wayward maraschino cherries, afraid to look right at her. Because then she might say, “Where do I know you from?” And what could he tell her? That it wasn’t so much that he remembered, but that he simply couldn’t forget?

Just within earshot a local dealer is selling to some Swedish kids — some product no doubt laced with Black Bleach™ (aka phraxifor). “No Black Bleach!” the guy hisses in answer to one of the kid’s questions. Wexler should warn them, but, as usual, acting on impulse is more trouble than it’s worth – last time he interfered with a sale, he had his left shoulder dislocated. From somewhere further down the beach, as if to remind him that there is an all-knowing God but that he’s a sadistic bastard, someone starts to play “Meet on the Ledge” on a seriously beater guitar. Badly, but unmistakeably. Their song.

An iridescent green cherry, on the end of the toothpick in his shaking hand, glows like a small, malicious planet. A celestial body harbouring the genetic code for its own destruction deep within its chemically sweetened crystalline centre.

It was back in 1999, the late fall. It was Livin’ La Vida Loca, it was Fight Club, it was Columbine, it was Y2K. It could have been fin de siècle jitters, it could have been too much caffeine, but some people were worried that the world might end. There were those who actually thought this might be a good thing. Others insisted the new millennium wouldn’t start until 2001, so relax. In fact, 2001 was when things would start to get really freaky, but how was anyone to know that back then?

Wexler had to elbow his way through the usual throng of protestors to get to the doors of the Toronto headquarters of the Oryx & Crake building at King and Bay. A gangly guy who looked like an out-of-work molecular physicist slapped ineffectually at Wexler’s head with a “Global Goon Squad” placard. Two robust nuns — on closer inspection men in drag — sang, “How do you solve a problem like Oryx & Cray-ake?” while bouncing Wexler back and forth between their padded bosoms as if he was a hacky sack.

Oryx & Crake had gone, in a mere decade, from a small family-run pharmaceutical concern to a monopoly-gobbling, global behemoth. Some said the CEO — a woman with a nasal monotone and an unnerving Cheshire-cat smile — must have shaken hands with the devil himself. There were rumours the company was attempting to trademark the DNA of its shareholders, scraping away at the Canadian government’s feeble protective legislation and playing shinny with various international protocols. As Wexler crossed the spit-polished lobby, he could have sworn the twin busts of Watson and Crick mounted by the fleet of brass elevators both winked at him.

Up on the 28th floor the others were already drinking from oversized mugs and talking congenially among themselves. They didn’t look like the usual types who did the focus-group circuit for fifty bucks and the free coffee. Wex should know — over the past few months he’d done a dozen focus groups, including ones for a new talk-radio station pandering to lapsed New-Agers (too earnest), a rapping Ken doll, “Ice-K” (he’d borrowed a friend’s eight-year-old son who declared the product, “gay and creepy”), and Texas-style-BBQ-flavoured chewing gum (surprisingly good).

Wex felt as if he’d stumbled into an audition for Diesel or Dolce & Gabbana. These people were all freakishly attractive. There was a lean, pouty-lipped guy tossing back a classic Brideshead Revisited forelock. A skater kid with the skin of a baby and tousled, blue-tipped hair that perfectly matched his eyes. A preternaturally thin, bald Eurasian whose gender Wex couldn’t determine. An older woman who was a dead ringer for Susan Sarandon. An Ethiopian Susan Sarandon. And then her.

Warming her hands on her coffee mug was the most striking woman Wex had ever seen. Blonde dreads, an armoury of metal punched through her face, arms lush with tattoos, and a Catherine Tekakwitha t-shirt engulfing her small frame. The coffee steamed in tendrils around her face, wreathing it like an image on a Victorian Christmas card.

Catherine Tekakwitha, who are you? Wexler wondered. Are you the Iroquois Virgin? Are you the Lily of the Shores of the Mohawk River? Can I love you in my own way? He was giddily channelling Leonard Cohen, a nervous habit. When he did this, in his thoughts he actually sounded like Leonard Cohen.

He was interrupted by the efficient voice of the Oryx & Crake rep asking them to introduce themselves. Wex’s ears were still ringing with the reverb from Beautiful Losers, so he didn’t catch most of the others’ names. “Wexler,” he said. He never introduced himself as Wex. Not since Grade 5 when that substitute phys-ed teacher had smirked and asked, “As in Wascally Wabbit?”

Then Catherine T. said something like Suzanne, yes, Wex was sure it was Suzanne, although later when he will dream her it’s not words that come out of her mouth but something else altogether.

Wex hadn’t been paying attention to the Muzak piped into the room — it was just the usual white noise. But now a song was playing that was pleasantly familiar. Fairport Convention’s “Meet on the Ledge.” It had been his hippie mother’s favourite, even years after she traded her Jesus sandals for Reeboks. Catherine T. seemed to be humming along, bobbing her head. “Meet on the Ledge.” Wexler’s new favourite song.

“You’ve all signed your disclaimers?” the rep asked. She collected the forms and then held up a small Mylar bag and shook it. “Melts in your mouth, not in your hand.” Someone laughed, but it wasn’t actually funny, not in a ha-ha way. Oryx & Crake had been doing this lately, buying up the rights to classic slogans instead of doing its own creative, trafficking in second-hand nostalgia. Retro-branding.

“It’s candy?!” The Susan Sarandon look-alike sounded deflated. “I thought this was a drug company.”

The rep rattled the bag again. “We’re diversifying. Strictly over-the-counter ingredients. No Black Bleach,” she said, referring to the deadly street drug the company was rumoured to be trying to replicate in its labs, and winked. “Code-name Bliss. But go ahead, sample, and you tell me.” She slit the bag with her teeth and tossed it onto the middle of the table, small multi-coloured beads bounced madly across the glossy conference-room table like water in a hot pan.

Later, Wex would struggle to remember which colour he had first chosen. It tasted pleasant at first as he rolled it against his palate with his tongue, a silky texture and a cotton-candy flavour. Then his mouth filled with sand. He couldn’t speak, but his eyes were wide open. This is what it’s like to be in a coma, he thought, surprised by the clarity of his mind.

He could make out a startlingly violet bruise on the previously flawless neck of the angelic skate punk and a pallor that betrayed low white-blood-cell counts. Mr. Upper Canada College’s crisp, linen shirtsleeve was pinned up at the left shoulder, empty. The regal older woman’s already protruding eyes bulged even more, yellowed in their sockets, a rail-yard criss-crossed her inner arms. The androgynous Eurasian, expanded to the size of Jabba the Hutt, slumped in a jail cell, talking a stream of filth and nonsense. He would continue to see all of their damaged selves in the years to come whenever they invaded his dreams.

The fluorescent lights overhead squawked and wheeled about, dirty seabirds now, beach-combing for edible debris. Wex lifted his head from the sand and there was Catherine T. rockbound — his Andromeda chained to a cliff above the sea. A scaly creature lurched from the water, mythic, voracious, a Trump tower of serrated teeth and shipwrecked breath. Catherine T. opened her mouth and out came, not a scream, nothing so operatic, but a tiny person, curled like a fetus or a fiddlehead fern. She sent it drifting towards Wexler on a breeze, buoyant, still breathing. But Wex was no Perseus, no sandal-footed hero. It was all he could do to turn himself around, and run inland, as fast as he could, his quads clenching, breath sluggish in his pipes, cursing all those who would sacrifice their children to appease gods and monsters.

The lights above Wexler were humming almost inaudibly. The dreadlocked girl had her hand on his shoulder. “Are you diabetic?” she asked him. “Or was it just a sugar buzz?” He was drenched and slightly dizzy. She was leaning so close he could make out the components of her musky fug — sweat, patchouli, Jamaican beef patties, and jitter-bugging in and around it all something that smelled very much like fear. The others around the table looked mellow, blissed out. Wex’s hands cramped. Opening them, he saw he’d been gripping some of the candies so tightly the colours had run together, the red ones puddling in the middle as if he had blood on his hands. That, or stigmata.

How long, how far, can you run from a memory of the future?

Wexler, who turned thirty-nine last week, the same age Martin Luther King, Jr. was when he died (and Che Guevara and Fats Waller — all men of more ambition than Wex) makes a deal right here and now, standing on this remote beach, in this poor, beautiful, strife-torn country, with a mangled “Meet on the Ledge” wafting through the air, the Swedish kids tripping badly behind him, and Catherine T. off in the distance walking towards a stony outcropping that juts over the sea. He makes a deal, his heart in his mouth — as small and sour as a dried apricot — to do something. To stop running, to create something meaningful, to find someone to love, yes, to make a child even. To live.

His Mohawk saint appears rockbound now, one with the cliff, shading her eyes as she looks out over the ocean. The water has sucked far back from shore, leaving an expanse of virgin beach littered with gasping parrotfish, blue and black sea stars and harlequin shrimp. The colours are dizzying. Local children run and dance further and further out, giddy with the wonder of it all, spindly limbs pinwheeling. Only Wexler and Catherine T. see the water rise in a towering sheet, darkening the horizon, rushing towards them like a berserk colossus on a surfboard.

And Wex runs. Not inland as fast as he can, but towards the cavorting children, his arms spread wide, howling full-throated like the warrior he might have been in an altogether other life, in an altogether different time. »

Laundromat

“And you’re the only one

who knows the monster’s name . . .”

— Rae Spoon

I still hate doing my laundry around other people; the unmentionables, the noise, the children. I wrote to you from a laundromat before. Could you tell? Did it come out clean or littered with other people’s gossip and drama? Did I tell you about the girl from downstairs who asked me if you can reuse a condom that’s been through the washer and dryer?

I saw a photography show once on laundromats. Humans of New York sort of feel. Whenever I see art I think, I could do that. A friend once said that the point is not that there is talent in being able to do it but in thinking of doing it in the first place. I have been recording all of my ideas so that when someone does it I can tell her I did think of it too.

In university we had a program, “Letters for the Inside,” where prisoners would request information and we would do the research and write them back 1. My first request was for Kevlar (bulletproof shirts). I wasn’t sure if this was kosher or not. We were only given rough outlines of off-limit topics. I did it anyway. So I know a lot about Kevlar. We were warned we weren’t allowed to be pen pals, however. There was a separate bleeding-heart liberal program for that.

Anyway, maybe you get so much fan mail you’ve forgotten me. Don’t forget me—it’s not fair. You are the one who is supposed to be punished. You are the one with the faulty moral compass. I am the one trembling and moving and being asked about condoms as if it were an accusation in itself. I am the one in hiding. You don’t even have to cook. I am searching for your humanity. My sexuality is under lock and key. Wi-Fi has been cut off; mail returned to sender.

I wish I could reopen your case and light a match to it. I wish for all this and more and to forget the sound of you snoring. I could never sleep. And still don’t. I used to use the washers and dryers (two of each) in the apartment building but once I found kids having sex in there. Also, it is slightly more expensive and doesn’t have any extra large loads.

Do female prisoners get as much fan mail or more? Do they get any? Orange is the New Black is now all the rage; lesbian sex, prison bars, poor misplaced white girl—who wouldn’t want a bite? Am I tempting you? I hate when people say we’re all in prison, not because of its truth but its stupidity. You always get me going on things like this. They have driven me out of two neighbourhoods now. It isn’t legal what they did but who can argue with a sexual abuse victim? How ironic, I am automatically attached to your name, your fame, your crime, and yet you will not even write back. I just want to know why.

I saw you as I sat in the pub. Someone threw nuts at your head. It was a slow night. All my nights these days are slow. I’m tired of seeing your face. Maybe prison is like art. I could have done it, too, but I didn’t. People watch the prison shows, however, to see how different we are. For that escapist thrill and the charge of moral superiority. I have given up on such judicial language. We all have locks.

I believe the girl who asked about the condoms is dating the guy I found outside one night, lying on the small patch of grass. I couldn’t tell if he was dead or passed out. I asked someone to find out for me, for I didn’t want to be the one to stir him. He said he was fine, and gave me a nasty look. A look like—mind your own business, lady. The same attitude I was given when I called the cops because it sounded like a bad fight in the apartment next door. Now I don’t bother. I don’t even comment on the condoms or the lewd graffiti (street art—ha) or sidewalk chalk. When I was a kid I never would have thought of such things. But to react to it is just reinforcement. So I try to ignore the lewdness. Eventually you don’t even have to try to ignore it, you just do. When I’m really stuck I bring up you. You are the answer to every dinner party in the ’burbs and in this hole, this laundromat. So much so that I no longer think you’re real. They probably aren’t sure, either. They could Google you. They probably have. Do you remember Google?

Perhaps I’ve been watching too many prison documentaries. So many pages, so many words, and still no resolution. Just more pages and more words. More silence. In Al-Anon we are to make lists of all the people we have harmed, which seems to be everyone we have ever met, and I said I wasn’t going to apologize for a life no one should have had to live anyway. As if the verdict is always guilty for everyone involved. They tell us to pray, that God can redeem us. Foolish me thought we were there because our exes and fathers were behind bars and treated beer as a sport. Amends. I don’t believe I even believe in the word anymore. Sounds like a new brand of vodka—I’m putting that on my list.

I remember—suddenly—I was supposed to buy groceries. Milk and bread and such. I remember you telling me how you’d get milk from Starbucks, filling up an empty cup. I can no longer stand Starbucks, it feels like everyone there is a clone and every drink is named after Oprah. Maybe people have a point—we’re all in prison. Selfpity is so lazy. Why is it that I love the word loathe, I mean, what does that say about me?

Favourite word, no doubt. It fills me up, takes up the space.

It is 2:00 am again and I don’t know what to ramble on about. Too much, not enough. I want to sleep forever but not sleep at all. I want to find your other letters—the ones I buried. I want to collect keychains from other countries. I don’t want to be strip-searched ever again—not even by you. I stare at the lined paper and the lines form bars, keeping the words in.

Now it is 2:17 am and something hurts. I don’t know how to explain. I don’t want to explain, but it hurts. And I’m remembering standing outside the metro, waiting for you. Pacing. And all the people going on with their lives. It was spring, I believe, but sometimes it seems like it was spring in every memory I have.

No one talks about this stage. People only talk about being young or old, no in-between. The old ones pointing fingers, the young ones with middle fingers. Somewhere in the middle life is just too uneventful. After the broken heart, before the grey hairs, after the weddings, before the funerals, there are the divorces. Maybe this is enough for now, all that’s left is debating between coffee and tea. At least, it would seem that’s all that’s left. I’ve got to do laundry, still.

Have you made your amends? I assume not, for I haven’t heard from you. I’d rather you didn’t, to be honest. Do it with the priest. It is raining hard here. You can’t go for a walk without being baptized. Can’t step outside without being free. So I stay here with my Canucks heated blanket and my Paul Auster collected prose. I know, I know—Go Leafs!

Sometimes I like watching the dryer, it does form a sort of dissociative fugue. I feel as I imagine cats do—focused, in the moment, perplexed by the mechanical movements and colours—waiting for the attack—some people think that it’s crazy to talk to cats. For me it seems entirely natural; more natural than answering the girl about the condom or the street art or the hooligan or you on the tv and the beer and the salted nuts and the carrot cake in the fridge given to me by an old friend. I still don’t know why. She did it as one does after a tragedy—a real tragedy—or when one buys a house next door—she stood at the door and I stood at the door for what seemed like an extremely long period of time. All this considered, who wouldn’t talk to her cat? I’m not sure we’re supposed to have pets but I also don’t think anyone cares.

I imagine your cell like a shoebox, I imagine you inside. I imagine you sharing it with a mouse. And a string to connect my telephone to you through a peephole. I picture all of this and more because you say nothing. You just stand like a totem pole in the midst of my life. You know that in Native customs you aren’t allowed to resurrect a fallen totem pole?

And I imagine our therapist—And how does that make you feel? I imagine us. That’s all you’ve left me—I feel fucking fantastic, doc.

I remember writing this before and so many other times, too many times to remember and I remember ice cream and fall leaves and movies but sometimes I’m not sure if I’m remembering a movie or remembering my life. I am writing to you, I remember that; do I remember that or do I know that? Words are strange, like bunnies that run around and make smaller bunnies and claw at wires and I’m angry about the bunnies and breaking every rule about writing letters.

Instead I live in a place where rage is a currency and everyone owes somebody an apology. Sometimes it’s better still to forget. Yes, this is one of those times. And I’m getting some of that coffee now. Really, I don’t remember, not at all. I wish I could forget you but not forgive. This is how it’s done— the orchestral version of silence—a page turn.

I’m remembering the first time the silence overtook me. This time you were the teacher, you replace every character in every memory. I was eating SpaghettiOs as a child and a feeling of deep shame and no understanding of why, and this image keeps reappearing and I want to go save her, go step in, but instead I don’t move. Perhaps I have also been replaced. That image of the thermos remains; the tiny desk, though it wouldn’t have seemed tiny at the time. And how I ran to the sink to throw up during silent reading time. But nothing around it, not before or after, just the thermos and the sink.

Tell me about your cell again and I will tell you about the laundromat and the coffee. I will tell you about the condoms and the neighbours and the Al-Anon meetings. I will tell you because I’m not telling God; I’m not asking for anyone to remove my character defects, I’m not asking to be saved, I’m just wanting to write. Wanting someone to know. My laundry is dirty and my words are in bars. »

1. Letters for the Inside is run out of Simon Fraser Public Interest Research Group (sfpirg), SFU’s student-based social justice resource centre.

» Creative Non-Fiction

Curtains

1.

They were screening Opening Night, the John Cassavetes, at the Royal. It was Cassavetes’ birthday. Also my birthday. After the movie we were ushered out into the bitter December night and none of us could bring ourselves to leave straightaway. We huddled under the marquee, stiff-shouldered, rocking on our heels, producing crystal plumes that vanished on impact. Opening Night exhausted us: we needed to talk about it. The way people careen. The way the cameras and cuts carve out blinkered geographies. The way exposition blooms in elision. Of the three of us it was Anna who had the most to say. She proposed that Gena Rowlands, the Rowlands character, that is, was destroying herself to become a character, the character the Rowlands character, an actor, is playing on stage in Opening Night, alongside the Cassavetes character. Anna’s comment cut to the heart of something worth huddling about: we all, or me, at least, but let’s say we, destroy ourselves, wholly or in part, to fulfill roles set for us by us or by another or in collaboration, whether out of aspiration, projection or desperation. Though a self is a hard thing to kill. Opening Night is in part about acting, in part about aging, in part about being present, which in part involves accepting age, which might also be regarded, in part, as a thing that destroys us. “And now we’re destroying ourselves by freezing to fucking death out here,” Dov said, shaking his eyebrows for emphasis. Dov was going home with Anna. I was going home to be alone.

There’s a story, perhaps apocryphal, perhaps exaggerated, about Laurence Olivier’s Othello. Olivier had been performing alongside Maggie Smith as Desdemona for four or five months when suddenly, for one magic night, everything seemed to come together, that perfect communion between actors collectively discovering the truth of the thing they’re making and an audience capable of receiving it. After the show, Maggie Smith found Olivier in his dressing room sobbing. “What could possibly be wrong?” she asked. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” she said. “It was perfect.” “I know,” Olivier replied. “It was perfect. And I don’t know why.”

Why does that night at the Royal keep coming back? It wasn’t the first time I’d seen Opening Night or the last. Dov is an actor, a wonderful actor. I was once an actor. Anna is not an actor. That screening, our exchange after that screening, forged an aperture, a punctum, as Roland Barthes put it. I saw something through Anna’s eyes I cannot now unsee. I see it all over the place. I see it in life’s muddle. I pass the first part of the pandemic revisiting films and see it clearly, exquisitely, in stories of actors (in one case a dancer), all of them women, inhabiting roles with varying ratios of ambition and repulsion, hubris and humility, desire and dread.

2.

“Time rushes by. Love rushes by. Life rushes by. But the red shoes dance on.” This is the impresario Lermontov summarizing the ballet based on Hans Christian Anderson’s The Red Shoes that will catapult his ingenue to stardom before toppling her headlong into the abyss. It’s also a summary of The Red Shoes, the postwar British film where Lermontov lives forever, which is also based on the Anderson. It was written, directed and produced by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger and photographed in Technicolor by maestro Jack Cardiff, its every frame rich, almost fibrous, its reds and blues especially, its shadows like velvet: it’s beautiful. The sequence where we see the titular ballet is both theatre and cinema: a stage expands endlessly, inanimate objects get animated, edits compress space and time while allowing choreography to luxuriate. This Red Shoes is about an extraordinary young ballerina named Victoria Page, played by Scottish ballerina Moira Shearer, who gets discovered by taste-making tyrant Lermontov, played by Austrian actor Anton Walbrook, and is nurtured to become a great artist at the expense of virtually all else that might occupy a life. This Red Shoes is about spiritual seduction, romance without intimacy, ambition as narcotic, art as eros. Victoria possesses the depth and discipline to embody Lermontov’s vision, but when she falls in love with the company’s resident composer, when she attempts to cultivate a space that doesn’t surrender to dance, when she attempts to forge a boundary between art and life, she’s exiled. She’s eventually invited back, but a terrible, irreversible triangle has been drawn. Early in the film, in the scene where they first meet, Lermontov asks, “Why do you want to dance?” Victoria responds, “Why do you want to live?” So it’s a zero-sum game, yielding a tragedy that’s fabulous and truthful. In the end the curtain rises, the spotlight is empty, the red shoes dance alone.

Cassavetes says, “We’re making a picture about the inner life and nobody really believes that it can be put on the screen, including me, I don’t believe it either, but screw it.” Rowlands says, “Actors will do anything they have to do to get the part right.” Rowlands also says, “You know you’re not being lied to,” with Cassavetes’ films. As precise and composed as Cassavetes’ films are rough and tumble, The Red Shoes shares with Opening Night an excess of attention to behaviour that registers as tenderness. Cassavetes says his films are about love. Most all of us want to be seen. We’re terrified of being seen. Film directors, good ones, they see you. They see the you the film needs.

There’s a scene in The Red Shoes where Grisha, the choreographer, tells Lermontov, “You cannot alter human nature.” Lermontov replies, “I think you can do better than that: you can ignore it.” On a day when she and I were struggling to negotiate something that had long seemed unfathomable, a day that in retrospect presented itself as the start of a parting, a parting meant, in part, to recover something annihilated but instead resembled annihilation, Laura turned to me and said, “You have to accept your nature.” My friend Heidi says that our friend Carol says that there comes a point in every long love story where each lover must forgive the other for being who they are. There came a point in the middle of my life where I found myself working to recover the thing I’d worked to conceal during the first part of my life. Nina Simone sings, “Don’t you know you’re life itself?” Leonard Cohen sings, “Looks like freedom but it feels like death. It’s something in between, I guess.”

3.

I work weird hours, writing, delivering food. I revisit films, records, books. I rearrange furniture. Françoise Hardy sings, “Et ton silence trouble mon silence. Je ne sais pas d’où vient le mensonge. Est-ce de ta voix qui se tait?”

Here’s what we know about Elisabet Vogler. She’s a prominent actress. In the midst of her last performance as Elektra, she suddenly fell silent and looked about her as though a shadow passed over her grave. After a minute of this silence, Vogler continued with the performance and afterwards made light of the incident with her colleagues. The next day, however, she remained in bed, did not go to rehearsal, and has not spoken since. She has a husband and a child. As Persona, Ingmar Bergman’s bottomless mid-sixties masterpiece, begins, Vogler has been admitted to a sanitorium. Vogler’s doctor tells Vogler’s nurse, Alma, that Vogler is perfectly healthy, both physically and mentally: she simply will not speak. We know what we know about Vogler because Vogler’s doctor tells us. And because the film shows us: we see Vogler, in close-up, on stage, in her minute of silence, eyes wide and fearful, surrounded by darkness. We know what we know about Alma, the nurse, because Alma tells it to Vogler, unsolicited, because Vogler doesn’t speak so Alma needs to speak, or because Alma, at least fleetingly, believes herself to be of interest. Alma is twenty-five and engaged to marry. She completed her nursing certificate two years ago. Her mother was a nurse. She rarely goes to the theatre, but she thinks theatre is important. When alone with Vogler, when Alma’s not around, Vogler’s doctor suggests that Vogler is suffering a crisis of faith in her capacity to apprehend truth on and off stage, that she has a desire to be unmasked, even annihilated, that she’s not speaking because she cannot bear to speak another false word. When alone in bed and unable to sleep, Alma tells herself that her life is sorted, her future determined. It is as though she is reading her life as a script and all she needs to do is follow along. Later Alma says that Vogler could become her, could enter her, study her, like a role, but that Vogler’s soul would be too big for Alma’s body. Alma is Spanish for soul. When Alma offers Vogler a photograph of her child, she tears it in two.

As a boy I had no talent for sleep. I spent wee hours in front of the television with the sound down. I never napped. My mother napped every day and, on occasion, would take me to nap with her. She would drift off to sleep almost instantly. Not wanting to rouse her, I would lay beside her, rigid, immobilized, waiting. Later, sleeplessness arrived with thoughts of annihilation.

Vogler’s doctor sends Vogler and Alma away to the doctor’s cottage by the sea. Vogler and Alma traipse the beach, read, take photographs, write letters, harvest mushrooms, compare hands. Because Vogler doesn’t speak, Alma speaks. Because Vogler remains opaque, Alma turns ever more transparent. There’s a scene in which Vogler, seated on a bed, smoking a cigarette, wearing a white nightgown, listens, without expression and with great attention, while Alma, tipsy, tells of an episode in which she and her fiancé were holidaying at a remote beach, but the fiancé was away and Alma was sunbathing with a strange woman, and both Alma and the woman, aside from their broad straw hats, were naked, and both were approached by two boys and a spontaneous sexual encounter, which Alma describes in detail, ensued between the four of them. This scene, in which one listens while the other speaks, is among the most erotic scenes in the history of cinema, because of the story and because of the listening. You wonder whether anyone’s ever listened to Alma. Soon after this scene comes another that is also erotic, eerie-erotic, brimming with little mysteries, though it involves no story. In this scene Alma, too, is silent. It is a Swedish summer night, the light silvery. (Persona, photographed by the maestro Sven Nykvist in black and white, is largely a two-hander, its every interior sparse in furnishings and devoid of décor. It is almost exclusively interested in faces and light.) Alma, in white nightgown, is in bed sleeping or not sleeping. From behind transparent curtains, Vogler, in white nightgown, silently appears. She enters Alma’s room like a ghost. Alma rises or is compelled to rise. Before a mirror or a lens, Vogler stands behind Alma, sweeps her hair from her face. Vogler and Alma peer into the mirror or lens together, as though their two faces are but two facets of one face: a Janus face. As Persona continues, the boundaries of the two women turn porous. Small, meaningful acts of violence accumulate. Vogler removes her voice because she cannot speak truth. Alma can only speak truth. Vogler listens. Alma gives and Vogler takes. Until Alma gives more than Vogler can take.

In Persona’s prologue a boy reaches out to caress a screen on which the faces of Vogler and Alma, which is to say the gorgeous faces of actors Liv Ullman and Bibi Andersson, dissolve one into the other in soft focus. Bergman says Persona grew out of the image of two women comparing hands. Hands, we come to understand if we live long enough, are one of the parts of the body that betrays age. Laura used to perform a joke: she raises her hands in the air so the veins recede and says, “Princesa,” then she lowers her hands so the veins engorge and says, “Monstruo.” In the first part of Persona is a scene comprised of a single close-up of the face of Vogler, the face of Ullman, who Bergman fell in love with while making Persona, while looking at Ullman, and the light fades so slowly as to render that face a landscape. When we become involved with someone romantically, we say we’re seeing them. In Opening Night, an actor gets into a car and an ardent fan outside the car reaches out to place her hand on the window that separates them. Cassavetes says a great shot makes you want to reach out to touch the skin.

4.

I revisit films. I listen to records, read. I work weird hours. I rearrange furniture, find things to get rid of, take unexpected naps. Tom Waits sings, “All the lies that you tell, I believed them so well. Take them back, take them back to your red house, for that fearful leap into the dark.” I think about actors and acting and actors playing actors. Anne Carson asks, “Do you want to go down to the pits of yourself all alone? Not much. What if an actor could do it for you?” It may be true that we all destroy ourselves to fulfill roles, but that process is typically so incremental as to be undetectable, an emergency so gradual it consumes whole regions of a life. Stories of actors greatly accelerate this process: showtime waits for no one. Waits sings, “Who are you this time?”

Opening Night is about the slippage between staged drama and personal drama, a wild, precarious, wayward slippage, a headlong topple to find truth in artifice. Myrtle, the Rowlands character, is playing the role of Virginia in a play called The Second Woman. The play is in previews in New Haven. At the start of Opening Night, after one such preview, an ardent fan rushes to Myrtle, embraces her, tells her that she’s seventeen, tells her she loves her. The ardent fan follows as Myrtle gets into a car. Ardent fan places her hand on the window of the car, the transparent curtain separating ardent fan from Myrtle. Ardent fan follows the car on foot in the rain as it pulls away, then is struck by another car, and dies. Myrtle sabotages rehearsals and performances of The Second Woman. During one rehearsal, Myrtle lays on the floor and says, “No more.” During one performance, she goes off-script to remind the audience that they’re watching a play. Myrtle is haunted by the ardent fan, who died at seventeen, exactly the age Myrtle was when she felt that all her emotions were available to her. Myrtle hates the role of Virginia because Virginia is overtly middle-aged and feels some essential part of herself slipping away. Myrtle says Virginia is “very alien to me.” During one performance, Myrtle says to the audience, “Time’s a killer. Isn’t it, folks?” Myrtle hates Virginia because if Myrtle does a good job playing Virginia Myrtle fears she’ll forever after be seen as older. Rowlands was forty-seven when Opening Night was released. Virginia is Rowlands’ given name: Gena is short for Virginia. Opening Night was written by Cassavetes, who was also Rowlands’ husband, father to her children, and co-star in Opening Night, which was also directed and produced by Cassavetes. Cassavetes and Rowlands’ body of work together constitutes one of the greatest collaborations in the history of cinema. They saw each other. With its fascination with actors, process and theatre, with its invocation of a ghost as a means to explore internal torment, Opening Night, which was released as Bergman’s most productive years as a filmmaker were drawing to a close, is easily Cassavetes’ most Bergmanesque film. With his unruly, catch-as-catch-can approach to shooting, his meandering narratives and disregard for standards of craft, Cassavetes is not what you’d call a Bergmanesque film director. Bergman and Cassavetes are two of my favourite film directors and Opening Night is where they meet.

Myrtle says, “I seem to have lost the reality.” Like Vogler, Myrtle despairs that she’s lost touch with truth. Like Vogler, Myrtle is terrified by truth. The Second Woman’s playwright, a woman in her sixties, promises Myrtle that if she says Virginia’s lines, Virginia will appear. Which makes Virginia sound like a ghost by whom Myrtle is seeking to be possessed. Myrtle is already possessed by the ghost of the ardent fan, or by some internal other. Myrtle says, “I’ll do anything I can to make a character more authentic.” Which in this story means pushing violently against the seams of artifice. Which means submitting herself to the violence of the furious ghost of ardent fan, or a furious internal other: a second woman. Which means sleeping with the play’s director, Manny, who is also Myrtle’s ex, who is also re-married, making his new wife another kind of second woman, who is played by Ben Gazarra, who co-starred with Cassavetes in a film called Husbands written and directed by Cassavetes. Which means flying to New York to visit a spiritualist, played by Cassavetes’ mother, and then abandoning the séance the moment the lights go out. Which means drinking alone or in company in her hotel room, which is so vast it resembles a stage set. Which means wandering the city alone on the day of the show’s opening and drinking until she can hardly crawl, much less perform, but performing anyway, leading to the final section of Opening Night, a nerve-wracking, riveting high-wire act that, as Anna put it, feels like watching a woman destroy herself to play a role. “Myths are stories about people who become too big for their lives temporarily, so that they crash into other lives or brush against gods,” Carson says. “In crisis their souls become visible.” A stagehand who adores Myrtle tells her he’s seen a lot of drunks, but he’s never seen anyone get as drunk as her and still perform.

I drifted away from acting when I was twenty-four. I continued to perform in a couple of my own plays, but I stopped auditioning. I felt unseen. I’ve since come to the conclusion that I was not capable, or rarely capable, on-purpose capable, of showing something of myself, of letting myself be seen. I only felt seen in quiet places, in intimacies, hidden from view but for a precious few. To be seen, I needed to be hidden.

Laura Linney says, “You struggle to find the play and then, one day, the play finds you.” I listen to records, revisit the films, push around the furniture. In love, one ‘you’ gets seen, while another ‘you’ gets hidden. Bob Dylan sings, “I don’t cheat on myself, I don’t run and hide.” Waits sings, “Time’s not your friend.”

5.

“Not to know yourself is dangerous, to that self and to others,” Rebecca Solnit writes. “Those who destroy, who cause great suffering, kill off some portion of themselves first, or hide from the knowledge of their acts and from their own emotion, and their internal landscape fills with partitions, caves, minefields, blank spots, pit traps, and more, a landscape turned against itself, a landscape that does not know itself, a landscape through which they may not travel.”

At the beginning of Clouds of Sils Maria, Maria Enders, a renowned star of stage and screen, is in transit. On a train going from Paris to Zürich, via her personal assistant Valentine, Maria learns that her old friend, Swiss playwright Wilhelm Melchior, who gave Maria her breakthrough role in a play and subsequent film adaptation called Maloja Snake, in whose honour she’s traveling to Zürich to accept an award, has died. What Maria and no one else will be told by Melchoir’s widow is that Melchoir, who was terminally ill, died by his own hand while overlooking the alpine valley where the strange phenomena that gave Maloja Snake its name, a serpentine cloud formation said to be a harbinger of bad things, occasionally, as though by its own caprice, appears. This valley, the site of Melchoir’s suicide, is near Melchoir’s house in Sils Maria, a remote settlement in the Swiss Alps where, some months after Melchoir’s death, Maria and Valentine will live as Maria prepares for a new production of Maloja Snake, more than two decades after the production of Maloja Snake that launched her career. In that earlier production, Maria played Sigrid, a young, single woman who is employed as the personal assistant of Helena, a woman who is twice her age and has a husband and children. Sigrid and Helena have a passionate, toxic affair that ends with Sigrid moving onto another job and another life, while Helena hikes out to the valley where the Maloja Snake occasionally appears, and there she disappears. In this new production Maria will play Helena. Maria is reluctant to take the role but is talked into it by its talented young director. “Helena scares me,” says Maria. “I feel too vulnerable for this.” While living in Sils Maria, Maria and Valentine spend a lot of time together, talking, drinking, eating, laughing, hiking, gambling, swimming, going to movies, running lines. “I wanna stay Sigrid,” Maria says. She says Helena is humiliated, pathetic, “defeated by age.” Valentine says Helena is sympathetic and complex. Maria weaponizes her laughter and talks down to Valentine, who is half Maria’s age. Valentine complains about Maria’s treatment of her, but Maria doesn’t change, or doesn’t change fast enough, and eventually Valentine hikes out to the valley where the Maloja Snake occasionally appears, and there she disappears.

I drifted away from acting when I was twenty-four. I felt unseen. Except in my own plays. At twenty-four I wrote and produced a play in which I played the protagonist, a protagonist who rarely speaks. He is a stranger, a traveler in an unnamed city, and everyone he meets believes him to be someone he is not, someone of great significance to their story, and in every case the protagonist, who is suffering from fatigue, hunger and a profound confusion, goes along with this, allowing others to believe he’s the one they’ve been waiting for. To be seen, I needed to be hidden in plain sight.

Maria is played by Juliette Binoche, who turned fifty the year of the film’s release. Valentine is played by Kristin Stewart, who turned twenty-four. Binoche is an actor of tremendous skill and insight who has become looser with age. She moves about more, her movements grounded in her core. Stewart was a fidgety actor and has become recursive and more interesting with age. Clouds of Sils Maria was written and directed by Olivier Assayas. When I interviewed Assayas and asked about the relationship between Clouds of Sils Maria and Persona, he said, “The moment I decided to make a movie about Juliette Binoche as an actress rehearsing a play, in this kind of rarified environment, I was already tiptoeing into Persona territory.” Persona, he said, “is not something you forget about or get rid of. It’s a ghost and it’s floating around.” Clouds of Sils Maria’s final image is one of light fading on Maria’s face, rendering it a landscape. As with Opening Night, Clouds of Sils Maria ends with the opening night of a play starring an actor who destroyed something to arrive at her performance, to apprehend some truth. The end of Clouds of Sils Maria reverses the end of Maloja Snake: the younger one disappears, while the older one moves on.

Let’s say we, all of us, but some of us more than others, at some times more than others, destroy whole regions of a life. The child, spouse or sibling; the inmate, pilgrim or citizen; the stateless, racialized or indentured; the solider, shepherd or revolutionary; the patient, prosecutor or politician; which part do you destroy?

You cannot unsee what you’ve seen. You cannot be unseen once someone has seen you.

David Berman sings, “Are you honest when no one’s looking?” »

References:

Assayas, Olivier, Clouds of Sils Maria, 2014.

Bergman, Ingmar Persona, 1966.

Carson, Anne, Tragedy: A Curious Art Form, 2006.

Cassavetes, John, Opening Night, 1977.

Cohen, Leonard, “Closing Time,” 1992.

Dylan, Bob, “Most of the Time,” 1989.

Hardy, Françoise, La question, 1971.

Powell, Michael; Pressburger, Emeric, The Red Shoes, 1948.

Silver Jews, “Smith and Jones Forever,” 1998.

Simone, Nina, “Wild is the Wind,” 1966.

Solnit, Rebecca, The Faraway Nearby, 2013.

Waits, Tom, “Who Are You,” 1992.

Buddy

It was after midnight, I was tired, and all I wanted was to heat up the bowl of leftover perogies I had waiting patiently for me in the fridge. Instead I stood at the door to my apartment as my neighbour stood at his, eagerly trying to convince me to “share your Internet, buddy.”

He’d called me buddy. That wasn’t a good start to the pitch. I don’t find buddy to be an endearing term; I think its true purpose is in condescension, a placeholder noun for drunks, and a way to ease marks who are about to get ripped off — “Buddy, do you really think we’d sell you a Zune that didn’t work?” He told me about his cousin who had recently moved into his place and how much he loved the Internet. The same weary eyed cousin who everyday would bring all of his earthly belongings from their apartment to the shade of the tree in front of our building. There he’d set up a sad bazaar and sell the pieces that formed his material life for a reasonable price. Eventually he even got a clothing rack that held what I assumed was every swatch he owned that wasn’t on his body.

Because we were neighbours and he loved his cousin he was willing to give me $10 a month to share my Internet. He suggested we could just string a cable from my router, out my balcony door, and into his kitchen window. It would be that easy. I waited for him to crack — “Just fuckin’ with you, buddy!” But he didn’t and just stood there, swaying like a tetherball stuck in its final revolution around the pole. Did he really not know about Wifi? I said I’d think about it and went inside.

For days I dreaded running into him. Saying no wouldn’t even be the hard part, I pride myself on my creative kyboshing — I’d love to but my Mom and I have our weekly Law and Order: SVU Skype date tonight — it was the after, the post-no unknown that worried me. I hardly knew the man but had heard his temper banging and clattering through the walls numerous times before. What if he turned on me, and his unibrow, which was so thick and even his cousin could of used it as a knick-knack rack at the bazaar, folded like an accordion in rage?

That was probably a bit of an extreme hypothetical, mind you. It was actually a pretty innocent request. I’m sure his eyebrow would stay level and he’d accept my refusal politely. Neighbourly. I was probably not being neighbourly by denying him. I mean, it wouldn’t be that big of a deal, I could just give him my Wi-fi password and pocket an easy ten bucks a month. That’s two tall cans and change to spare. There’s always the risk that his cousin is one of those people who for some inexplicable reason downloads porn instead of streaming it, which could potentially tie up my bandwidth, but that’s not the end of the world. That’s something I could layout in a few ground rules beforehand. Perhaps give him a list of preferred sites to visit — a top ten. I could probably even spice up the deal: one of his cousin’s paisley button-ups a month on top of those ten big ones.

I saw his cousin a few times in the days following our midnight encounter. He’d been fanning himself with an old whodunit as he stood behind the small folding table that acted as his storefront. He looked uncomfortable. Shifty. Like his underwear was riding. I felt for him. I couldn’t tell if I was feeling pity or shame. This middle-aged man had fallen to the point of living on his cousin’s couch, had to resort to selling the physical remnants of his life to survive, and I couldn’t even see past myself to let him have access to an online relief. The Internet was now a basic human right according to the U.N and I was depriving him of it. I was a tyrant. A twenty-something despot. I waved to him as I walked by, holding my open hand up and out for a little too long before realizing what I was doing and quickly pulling it back in. He gave me a slight nod and looked to the ground. Eye contact wasn’t allowed with the supreme leader.

A couple days later I came across his table set up a few blocks away on a grassy patch across the street from the SkyTrain station. The landlord must have had a talk with him — I imagine it would be tough to convince him it was still a casual weekend yard sale on a Wednesday. The shirt rack still didn’t have a dent in it. The clashing patterns of the fabrics were like one of those Magic Eye stereograms; I unfocused my vision to find the hidden image — a dachshund with glasses?

“See anything you like, buddy?” It wasn’t a dachshund. The cousin pulled a grip of shirts off the rack and held them out at his sides.

“What size are you?”

“No thanks.”

“Huh? You want medium? You look like large. No offense.”

“No, I mean, uh, I was just looking.”

“Ah, okay. Have good day then, buddy.” His eyes fell to his feet again. I felt like Kim Jong-un on a factory tour, just stopping in to make sure the people I was stripping of their rights and freedoms were making the lubiest of lube possible.

There was in fact a limit to how much sushi I could eat. The limit was a lot and I reached it like a triathlete with shin splints falling over the finish line. My body picketed the gluttonous amount of tuna, yam, and avocado, bubbling inside of me. Hey-ho, we won’t go!

At the front door to my building, standing between me and taking my internal protesters to porcelain court, was my neighbour. It had been over a week since I’d seen him and I had forgotten about his offer, his eyebrow, and his cousin who loved the Internet. I had to make my decision right there and the answer came quickly: I would say yes, I would share my Internet. I would grant his cousin the ability to get lost in ’90s nostalgia listicles and to buy peanut butter online.

His eyebrow rose like a church steeple as he opened the door. I readied my response.

“Do you live here?” He stepped in front of the entrance, protecting our building from me. I didn’t know what to say. I was fully prepared to accept this offer made to me by a man, my neighbour, who now apparently had no idea who I was.

“Yes. I do.” With a grunt he continued on inside and I followed him up the three flights of stairs and down the hallway to our apartment doors where we’d talked only days earlier. He looked at me briefly before going in, dead bolt locking with a clunk. That was it. He didn’t mention his cousin or the cable from my window to his. He said nothing. His eyebrow didn’t so much as quiver. I opened my laptop. Its video streaming was quick, its web pages were loading with unparalleled quickness, my bandwidth was high, and that’s the way it would stay. »

Youth Laid Waste

“Very early in my life it was too late.” —Marguerite Duras, The Lover

When I was a teenager I skipped school so much I’d get taken aside by my teachers and told I’d missed the most school of anyone in the history of our little Montreal-West, public-for-smart-kids prep school. I brushed them off and kept writing myself doctor’s notes and answering my phone in French when the school secretary called, pretending I was my mother, saying, “Yes, Melissa has another terrible tonsillitis, depression, stigmata, mononucleosis, but she should be back on her feet in a week.” I was still in band, on the school paper, got decent grades in enriched biology. But, having been raised by artist wolves, I was oftentimes overwhelmed by the normalcy of my peers’ day-to-day. Teenagers seemed like children to me, their mothers still bought them clothes and made sure they got haircuts and gave them curfews; sometimes their parents still cut up their apples into quarters to make it easier for them to eat with their braces. They went to camp, they knew how to play softball. I had no idea how to relate.

So I’d stay home and carve out some time for myself.

When I was in my mid-teens, after a series of unfortunate episodes, including one in which my stepmother tore up the side of my face with her thumbnail, muttering, “I hate you!”, I decided to move in with my mother full-time.

Although my mother had no permanent position, she made a living teaching art at both elementary schools all over the island and at a few universities in and around Montreal. She was out of the house in the fives each morning. I’d wait ’til she left—sleeping past dawn was not difficult for a teen. And then I’d run myself a bath. I’d put on my mother’s blue and white Japanese kimono, feeling bohemian and nearly-womanly. I’d reheat coffee from the morning’s pot. Eat a couple of teaspoonfuls of lemon curd from the jar. Play my mother’s The Best of Barbra Streisand record. Give a couple cursory glances to her ’70s women’s erotica—a.k.a. My Secret Garden—then leaf through her stash of ’70s craft magazines for outfit ideas. And then I’d head to the front of the apartment and flip on the computer—one of those Macs from the early ’90s, square and friendly as a miniature Westfalia—and start writing. I’d sit there totally blissed out from writing, a big cup of reheated filter coffee, my poorly self-cut, hennaed mess of orangey hair smelling strangely of herbs. Happy happy happy.