- Art

- & Commentary

- & Creative Non-Fiction

- & Fiction

- & Photography

- & Poetry

- & Reviews

- | Back Issues

- + Blogs

- + About

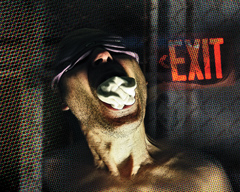

Erasure and Exile

Image by Derek von Essen

How are we to think about Vancouver, our young and beloved city beside the sea and under the mountains? Popular conceptions, government and advertising rhetoric, would have us believe that we are perfect, innocent, beautiful, without a past. Popular and not-so-popular fiction, on the other hand, gives us an account not so easily separated from past and present hard realities. For such a young city, Vancouver’s history is marred by monumental acts of racism, violence, and neglect. The mining of our bygone days reveals this without much effort. But now our non-fiction recitals offer us up as a commodity, a sacrifice to the inhumane machinations of the market, erased of a past both good and bad. How can we know ourselves in this arrangement?

Describing the hostility towards Canadians of Japanese descent and their eventual internment outside of the city and province in the early 1940s, the semi-autobiographical Obasan by Joy Kogawa presents an eerily familiar Vancouver cityscape, but one where the acts committed by the white majority ironically (or, perhaps, not ironically at all), echo the acts of Nazi Germany against European Jews:

Grandpa Nakane at Sick Bay? Where, I wonder, is that? And why is it the cause of distress? Is Sick Bay near English Bay or Horseshoe Bay? When we go to Stanley Park we sometimes drive by English Bay. Past English Bay are the other beaches, Second and Third Beach where I once went to buy potato chips and got lost…

Sick Bay, I learned eventually, was not a beach at all. And the place they called “the pool” was not a pool of water, but a prison at the exhibition grounds called Hastings Park in Vancouver. Men, women, and children outside Vancouver, from the “protected area”—a hundred-mile strip along the coast—were herded into the grounds and kept there like animals until they were shipped off to road-work camps and concentration camps in the Interior of the province.

The naming of popular geographical features of the city against the gathering inevitability of expulsion is a cruel irony. Places that are almost certainly associated with leisure and memories of happier times with family and friends become landmarks of a city that demanded a people’s exile. Besides the loss of property, homes, and businesses—which were never returned—less tangible things like memory and the sense of identity that comes with an attachment to a place, were stolen as well.

Throughout Obasan, silence, the inability, or more significantly, the refusal to speak of the past, is presented as forgetting, a willful amnesia—an unnamed presence, but one that is necessarily identified precisely because of its absence. Here, silence is a starving dark beast living in the hidden corners of the night. Naomi, the central narrative voice, describes her aunt’s domestic putterings:

She seems to have forgotten her reason for coming up here. I notice these days, from time to time, how the present disappears in her mind. The past hungers for her. Feasts on her. And when its feasting is complete? She will dance and dangle in the dark, like small insect bones, a fearful calligraphy—a dry reminder that once there was life flitting about in the weather.

She laughs a short dry sound like clearing her throat. “Everything is forgetfulness,” she says.

The subjects of forgetfulness are the victims of internment, but as Naomi’s other Obasan, the passionate and vociferous academic aunt Emily, points out, theirs is largely a psychologically internalized reaction imposed by a surrounding culture that demanded Japanese Canadians’ disappearance:

The Vancouver Daily Province reported, ‘Everything is being done to give the Japanese an opportunity to return to their homeland.’ Everything was done, Aunt Emily said, officially, unofficially, at all levels and the message to disappear worked its way deep into the Nisei [second generation Japanese-Canadians] heart and into the bone marrow.

The voice that Obasan gives to “the silence that will not speak,” demands acknowledgment of the past, not only from Naomi and her generation, but from the reader as well—perhaps a reader with only a cursory knowledge of his or her city’s history. Towards the end of Obasan, the reader is offered a catechism of sorts:

Where do any of us come from in this cold country? Oh Canada, whether it is admitted or not, we come from you we come from you…We come from the country that plucks its people out like weeds and flings them into the roadside… Where do we come from Obasan? We come from cemeteries full of skeletons with wild roses in their grinning teeth. We come from our untold tales that wait for their telling. We come from Canada, this land that is like every land, filled with the wise, the fearful, the compassionate, the corrupt.

Brett Josef Grubisic’s comparatively light-hearted, but ultimately tragic, novel The Life of Cities offers an account of Vancouver during the late 1950s that straddles antagonisms between personal freedom and oppressive social constraints—both self- and externally imposed. Early in the novel, central character Winston Wilson makes a literary identification:

Years ago, he’d read Alexander Pope’s couplet about mankind being born on an isthmus between two places—the feral and the angelic—and still felt it was apt. The two qualities were intertwined, fatally entranced by one another like Narcissus and his reflection.

Winston compares himself to Oedipus, the once king of Thebes: he lives with his mother, his father is gone, and one of his feet is damaged. Winston is aware of these similarities, amused even, as much as they relate to literary history—he is, after all, a librarian in the stuffy fictional Fraser Valley town where he lives. However, in relation to the underlying psychoanalytical bearing of the story of Oedipus, he is completely unaware—that is to say, he is unaware of himself, not as unconscious and metaphorical murderer and usurper, but as a closeted gay man. Winston, in his denial of who he is, however much he is unaware, has always been an outsider, has always been banished to the fringes. But by virtue of his outsider status he is neither comfortable in the straight-laced world of fictional River Bend City, nor does he shed his uptight nature when he discovers a gay subculture moving about the seedy bars and dark corners of Vancouver.

An excerpt from “Erasure and Exile: The theme of expulsion in contemporary fiction of the Terminal City” by Patrick Mackenzie.

From Issue #54/55. On newsstands any day now!

© 2000 – 2025 Subterrain