- Art

- & Commentary

- & Creative Non-Fiction

- & Fiction

- & Photography

- & Poetry

- & Reviews

- | Back Issues

- + Blogs

- + About

Alvin Karpis & The Great White Zeppelin

I am thirteen years old and I’m sitting in my South Van bedroom spinning 45s on my RCA Victor mono record player—The Who, The Animals, The Stones, The Yardbirds, Them—‘Van the Man’ belting out “G-l-o-r-i-a” before anybody knew anything about the little brown-eyed girl “down in the hollow, playin’ a new game”, or who the hell Van Morrison was—and, of course, The Beatles. The b-side of The Who’s “Pinball Wizard”—Keith Moon’s “Dogs, Part 2”—makes me crazy with glee. I want to scream and bounce off walls. I have my first set of sticks and a white pearl mix-’n-match set of skins in the basement. I thrash wildly along with the Moon Dog. Fuck—it’s 1969 and I’m rockin’ and rollin’ and ardently working on my self-image!

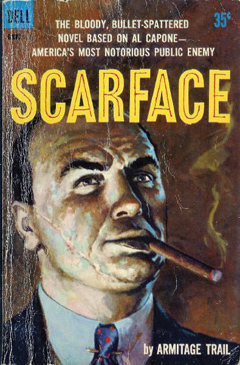

In the second drawer of my chocolate-brown, laminated dresser (underneath my gonch and socks) is a dog-eared copy of Scarface, (the Armitage Trail Dell original, with the fantastic cover illustration by Victor Kalin), my favourite book at this juncture in my “literary education”. Al Capone shooting Chicago to shit.

And I have recently procured a new book that I tuck in there too: Public Enemy Number One: The Alvin Karpis Story. These sensational and violence-packed paperbacks are hidden in my drawer because I fear they will be confiscated, that their presence will result in parental retribution, some sort of punishment. I dread the idea that they may be taken away, discarded as subversive trash. Already, at thirteen, I am aware of the power of the written word, the threat posed by certain brands of writing. Writing that advocates alternative lifestyles, counter ways of seeing the world, that undermines the status quo is to be monitored, kept under wraps (oh those brown wrappers that hid the erotic world!), and, in some cases, censored entirely.

There were no books like these in our house. We had the standard set of Encyclopedia Britannica, titles on wwii, and that was about it, with the exception of a coverless copy of John Cleland’s Fanny Hill that I found tucked away behind the encyclopedias.

Whose copy was that anyway? My old man’s? My brother’s? Some boyfriend of my older sister? Could it have been my sister’s?

My most memorable book-related experience up to this point in my young life had been an ass-paddling at a Bible Study class. I was paddled for criticizing the “good book”. I said it was boring and it was, at least the way it was being taught in this class. The boredom factor had more to do with the method of teaching than the actual content. Even I knew that. We were handed colourful “learners” that looked like they were written and illustrated for toddlers and were instructed to read along in a “Dick and Jane” story fashion. I hated it.

For my outspoken critique I received three smacks on the butt-side with what looked like a cheese board with a long handle. The paddle section had holes in the wood, holes the diameter of a large piece of blackboard chalk. It looked strange, as though it had been specially designed to inflict pain on young, insubordinate brats like me. What were those holes for? So my flesh could sink in, forming huge pink blisters on my skin? To allow the blood to spurt forth upon contact? I wanted to kill the minister, the father, whoever the prick was, but I couldn’t. I was too small and I didn’t own a Tommy gun. Again, I was subject to a lesson in the peculiarities surrounding books and reading. I learned the potential consequences of a harsh critique. Several years later I would visit this church again; not to desecrate the building or the vestments, and not to bust the paddle that had humiliated me when I was so young, but rather to steal a microphone. We were forming a band.

I am surprised to discover that Scarface thrills me like nothing else my teenage mind has come across—but in an entirely different way than Fanny Hill will thrill me about a year later. It makes me want to be a gangster, a gun-toting mobster swinging from the sideboard of a speeding car, machine gun under my arm, blowing to smithereens everything that decent society has to offer, every alluring set of shackles it throws at me. It demonstrates the power of the imagined world, the emotional freight that can be conveyed by narrative; it showed me the power of the story.

I knew these guys were bad. They killed people—lots of people—indiscriminately, for money and their own perverse sense of power. At least that’s what my teenaged mind imagined. But the most seductive thing that came across in these books was that these guys made their own rules. They were pegs without a hole and they took shit from no one.

I wanted to be a guy like that. But all these guys were from big American cities like Chicago and New York. I lived in an oversized logging town filled with drunken rednecks on the northwest coast of the Pacific. Was it even possible to live a life of anti-authoritarian rebellion in Colonial Canada? But wait, that other guy, that Karpis character—he was Canadian. Born in Montreal, his family moved south to Kansas. It was there while doing a stint in the pen that he linked up with the Ma Barker Gang, did atrocious deeds all across the country and ended up on Alcatraz Island for twenty-six years. Now there was a role model for an angry teen!

Then the drinking started and our apparel (and mood) shifted from the soft and colourful style of the mods to the darker gear of the angst-riddled rockers. Imagine Eric Burdon, 1965. Hair like slick cake icing drooped across my forehead and over one eye—arrrgh, I have more attitude than I can stand. Tight jean jackets, and even tighter stretch-denim jeans—why isn’t the whole world made of denim? Why don’t we have denim sheets! Denim curtains! I don’t know the answers to the questions cascading through my head but I do know I have no time to wait for the answers. The answers that never come! Instead I’m flippin’ on another disk, hiss and pop and then—Boom!—the room fills with The Kinks’ “You Really Got Me”! Or “All Day and All of the Night”. Fuck! I am sooooooo misunderstood!

We drink more and get into fights. Snoop boots, big brass belt buckles. Trouble with cops, trouble with parents, and we soon come to realize that drunken obnoxiousness does not an outlaw make. We are rebels desperately in need of a cause. Then in the summer of ’69 the bomb drops, and the bomb is in the form of a zeppelin—Led Zeppelin #1 in all its exploding phallic intensity. That spinning, red & green Atlantic label and what it delivers blows the hinges off everything. Our world is never the same again. Now we have a sound embodi-ment of a Code of Ethics, a Code of Conduct, and prior to this moment nothing has grafted this particular combination of angst and foreboding into music: a guitar that sounds like a huge beast being disemboweled at the bottom of a dark steel tank while microphones amplify the event and jettison its howls through a Leslie speaker on full bore. We are gobsmacked, dumb-founded and it is all we can do to keep our heads above the tsunami of sound that follows. We know nothing about cultural imperialism and how we are being formed by the British invasion of music and America’s cultural monopoly of this continent. We do see, however, that we can fight the machine with music and words instead of guns and knives. The appropriately dubbed “axe” will deliver the foundation blows necessary to shatter Canada’s insipid cultural bedrock. And with any luck, down will go Don Messer’s Jubilee, The Tommy Hunter Show, and Anne Murray’s entire back catalogue.

I go forth in search of our own Canadian literary outlaws and start this magazine so they will have a place to hide out. »

From Issue #53.

Back to top© 2000 – 2025 Subterrain